Composition and Narrative

Last week we looked at the importance of style and characterisation in picture book illustration. This week I'm going to waffle on about the other two things that make a winning illustration portfolio - composition and narrative.

The point of picture book illustrations are not (just) to add decoration to a written book, they’re there to convey not only the overall message and atmosphere of the book (style), but also, more practically, to tell the story. It is very rare that the words alone tell the story in a picture book - indeed often they don’t even make sense separated from the illustrations - the two work in tandem.

So part of the illustrator’s job is to decide which bits of the story need illustrating - what are the key moments, and then decide how best to portray that moment in a single frame - much like a film director - you decide on the angle of view, the composition, lighting and key action necessary to enhance and add to the drama of the narrative.

Composition

Most picture books are 32pages long - with end papers, title pages etc. that usually leaves 12-14 double page ‘spreads’ - so each story needs to be broken down to , say, 12 ‘scenes’ - but it's up to you how to ‘shoot’ the scene.

Practical things to bear in mind when composing your illustrations;

Size - ‘trimmed page size’or 'tps' is the final size of the page. Every publisher has 1 or two different standard page sizes their books adhere to - when putting together images for a portfolio measure a few books first to see what kinds of size/proportions are standard and work to those. An A4 -sized and proportioned piece looks amateurish.

Bleed - All publishers require the illustration to carry on outside of the tps, to allow for movement and discrepencies when the pages are being cropped and also to allow the designers to move your illustration around on the page a little if desired. If you're undertaking a commissioned piece the publisher will specify how much they require but it will be at least 5mm . They also won’t want any important elements within 5-10mm of the edge for the same reason.

Gutter; The crease down the centre of the spread - you MUST bear this in mind for your composition - there should be no detail on or too near the gutter.

Text placement - you must leave enough room for text - normally more than would allow the UK text as other languages take up much more room!

So... you have your text, your page size, your character sketches, now you need to plan your book out...

Storyboards

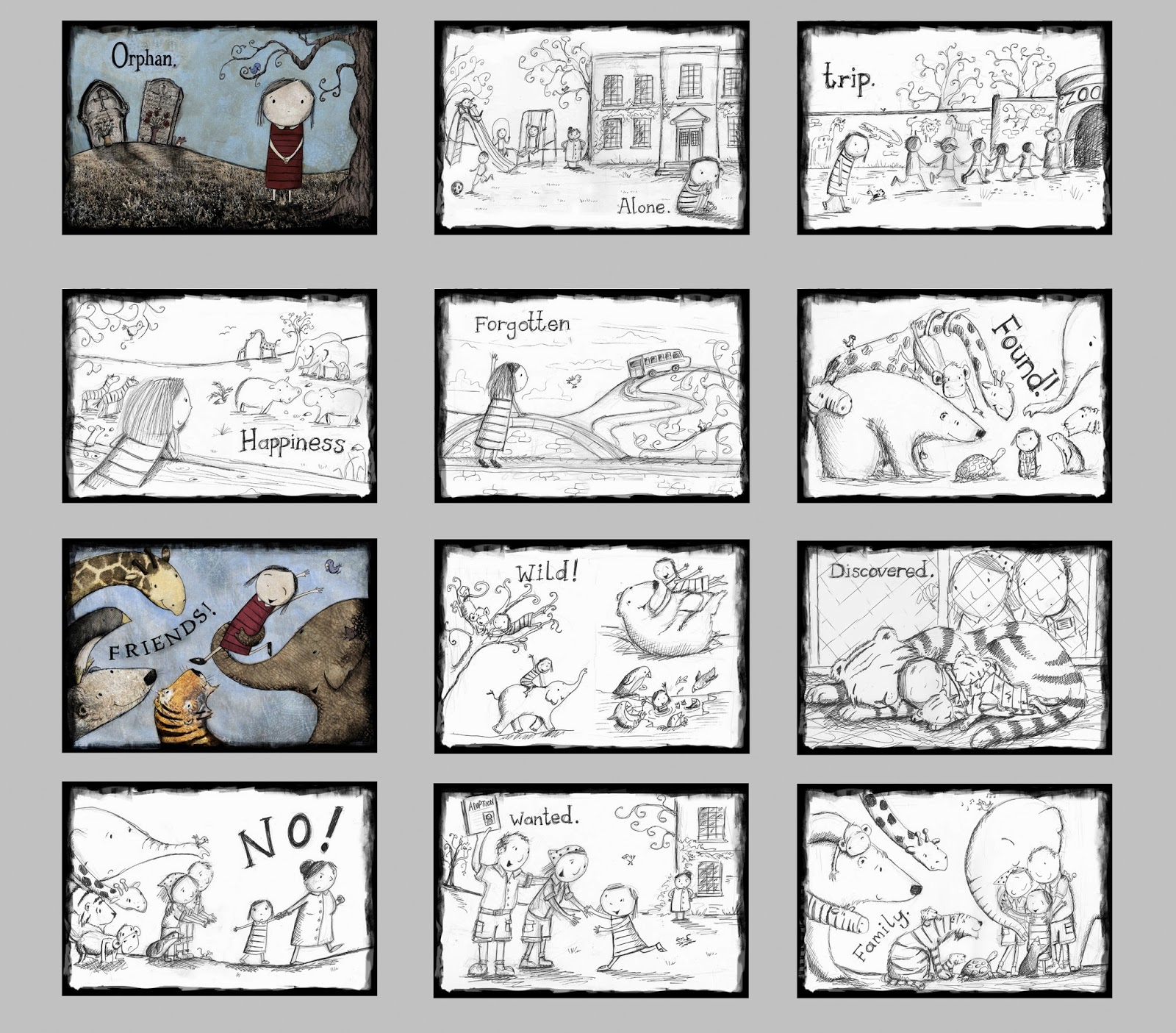

Storyboarding is essential part of planning a picture book. Telling a story in 12 spreads is an art that requires you to tie the elements of pace, composition and colour together - storyboarding makes that possible and lets you see at a glance how to improve these elements.

Can be very rough and sketchy or very detailed - everyone works differently but the storyboard is the time to try out different compositions, different text placements, pacing, even colour schemes.

Basically, draw 12 rough rectangles for your 12 spreads and start sketching up rough ideas for compositions on each spread, eg.

Use this method to try different compositions for the same spread;

So what makes a good composition?

- Visually appealing

- Helps (rather than hinders) the narrative

- works with the text

- makes good use of the space allowed - including white space, the gutter,

- Varied within the book - close-ups, different angles, viewpoints, full page scenes or small spot illustrations or 'vignettes'

- Action - not static - either emotion or action conveyed to the reader. Nobody wants to see two character in conversation for spread after spread in a book. Vary it. If there's no excitement in the text, create some in the illustrations.

Try to get movement, action and exaggerated emotions into your spreads - and try to get accross what is happening with or without the text. I hope this 'submarine poop' spread from 'Mr Poopy Pants (Lion Hudson, due out in June) speaks for itself!

But much like when we looked at what makes a good picture book text the answer really only lies in other successful books, pouring over them, really looking at what makes the artwork work so well, when you do this you'll start to learn what works and what doesn't.

Never underestimate the use of colour - in my forthcoming book with Lion Hudson, 'Missing Jack' a difficult subject of the death of a pet is covered so on this spread, the saddest in the book, I wanted the colours to be very muted and the elements on the page to be sparse. Later in the book when Toby starts to accept a new pet into his life the colours pick up again, matching his mood.

Narrative

When potential publisher looks through your portfolio one of the things they're looking for is great storytelling ability. Without reading the text can they already get a sense of the characters, emotions, plot from your illustrations alone? Do your illustrations add more story to the text than was there to start with? Hidden depths for children, particularly older readers, to discover?

Two new spreads from Fat Fox book 'Happy Hooves' due out later this year. Both spreads are set in the same spot but I wanted to vary the colours of the background from spread to spread so that the book didn't feel static so in the second spread I've used patterns and colours from the pig character, the star of this scene, to colour bits of the background, I've also taken a drastically different 'camera' angle from the first spread to frame the scene. Artistic license is what it's all about in children's book illustration!

Activity

Draw 4 rough wide rectangles on your page with a line down the middle to denote the gutter. Pick a random scene from this list and sketch out 4 different versions of it. Which works best? Why?

Homework

Work up a finished spread - can be a character or text you’ve been working on, something fro the list above, or a classic nursery rhyme or favourite book from your childhood (think 3 little pigs, Little Red Riding Hood, Goldielocks, etc... but maybe with modern spin!)

Remember to;

design your characters first

plan your composition first - think how you could improve it

do a pencil rough before going to colour

Extra homework if you have time.... storyboard an entire book - again, either your own or a classic, think in terms of 12 spreads.

NEXT WEEK: How to put together a plump, beautiful and irresistible portfolio and market your work to needy greedy publishers.